What is Resonance and Why is it so Important?

Resonance is experienced, and even identified as responsible for the forms of what we perceive, observe, or infer based on it - an atom, a flower, planets, galaxies.

Figure 1. From “Resonance: from swings to subatomic strings” — resonance appears everywhere, from playground swings to molecules absorbing light. - Bernie Hobbs

Resonance binds together the different elements that make up reality and allows interaction between them. It is the main factor for feedback to be possible, the conduit, shall we say, through which the exchange of information happens: the external can penetrate the internal, and vice versa; the internal can manifest itself outside. The condition for that channel to be opened, and made available, is the coincidence in energy; that the inner and outer energies are compatible. i. e., that they have the same frequency.

In general, we could say that everything around us is vibrating or is vibration. Light or electromagnetic fields is a free propagating vibration in empty space. It is usually depicted as a waveform in 2D, when in reality it moves in 3D following a helical motion, and it is a transverse wave because it vibrates perpendicular to the direction of propagation of the wave (green and red oscillating arrows):

Figure 2. Electromagnetic waves are vibrations that propagate through space. They move in 3D with a helical, transverse motion, oscillating perpendicular to the direction of propagation (illustrated by green and red arrows).

The green and red oscillating vectors are the electric and magnetic component of the wave, respectively. For more on electromagnetic fields, please read the ISF article “The Origin of Quantum Mechanics I: Tle Electromagnetic field as a Wave”.

When the vibration is not happening in empty space, but through a material sample, then the wave is known as a sound wave, and its propagation speed will depend on the material nature of the sample. It will be a longitudinal wave, meaning that the vibration occurs in the direction of propagation of the wave.

Matter is also vibration, which is confined in a certain volume in space. All objects, even if static, have lots of internal vibrations, its atoms are basically, pure vibration. And the internal modes of vibrations - also known as vibration modes- are particular for each atom, and molecule. These are the fingerprint of the object, it being a quantum particle, such as an atom, or a tennis ball, or a planet, or a star.

Each object has its fingerprint, which are its own modes of vibration. These are defined by its form and atomic/molecular composition. For example, if we take a simple molecule of water, composed of one oxygen and two hydrogens, its normal modes of vibration are depicted in the video below:

When an external vibration (remember that energy has an oscillation or vibration associated with it, with frequency f) strikes the object, if that vibration (frequency) coincides with any of the object's modes of vibration (which have their frequency as well), the object will absorb that energy and that normal mode of vibration will amplify its amplitude (it will vibrate more intensely, analogous to higher sea wave amplitude).

This principle is what makes, for example, that a glass vessel breaks when some acoustic vibration around it coincides with any of the normal or proper modes of vibration of the glass, so that if the volume (intensity of the sound) is high enough, the glass will absorb that more energy, its atoms will have more kinetic energy that is amplified by this is known as the resonant condition, until the glass breaks (loses its shape, unable to withstand so much internal energy amplified by the external).

Likewise, an object that is made to vibrate (it does so at its own frequencies or modes of vibration), can stimulate the vibration of any other object around it that has some mode of vibration of its own that matches its own. Please find the video below:

Sound is, therefore, consequence of resonance.

Color, too, is another consequence of resonance.

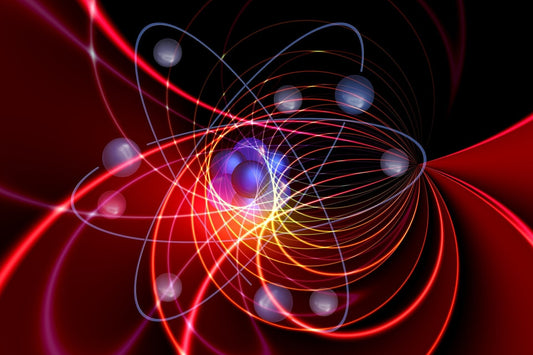

To explain the nature of color, we first would have to address some quantum mechanics concepts, some of which is summarized in the figure below.

Figure 3. The hydrogen atom consists of a proton and an electron, both vibrating at specific quantized frequencies. When white light interacts with the atom, only certain frequencies are absorbed, exciting the atom briefly. The resulting emission of energy produces the hydrogen atom’s characteristic emission spectrum.

The simplest known atom, the hydrogen, is mainly composed of a proton and an electron, where both are basically confined vibrations at different frequencies, also known as normal modes of vibrations. This means that they are allowed to vibrate only at certain frequencies, defined by quantum mechanics. Their vibrations are “quantized”. Meanwhile, white light propagating electromagnetic oscillations, contains all frequencies of the visible spectrum, therefore, when it reaches the hydrogen atom, only parts of the electromagnetic spectrum can be absorbed by the atom, and it becomes “excited”. This excitation lasts very short time, it decays almost immediately, and the energies emitted by the atom can also be detected. This is known as the emission spectra of the hydrogen atom.

There are two ways in which one can measure the spectra, or fingerprint of the interaction between light and the atom: from the perspective of the frequencies of light that are missing from the original after they have been absorbed by the atom (upper section in the figure below), the resulting spectra is known as absorption spectra of hydrogen atom, or, by measuring the emission spectra of the excited atom. Both spectra are almost the negative one of other one, except that there are very small energy loses as heat, during the de excitation of the atom, and hence the energy emitted is smaller than the absorbed, its frequency is a little smaller; it shifts the spectrum a little, almost unperceived bit, to the red side, i.e., to larger wavelengths.

Figure 4. Each atom and molecule has a unique emission spectrum, serving as its “fingerprint.” Spectroscopy measures these spectra to determine the chemical composition of matter, with molecular spectra reflecting the combined vibrations of their bonded atoms.

The spectrum is particular for each atom, it is the fingerprint of each atom. The scientific technique that measures the spectra of elements is known as spectroscopy, and it allows to determine the chemical composition -atomic and molecular- of everything around us. Molecules also have their own fingerprint (which is more complex than for the atom, because there are many more modes of vibrations involved), because it can be decomposed in the different vibrations coming from its bonded atoms.

One of the most beautiful ways of looking at the periodic table, is thought the emission spectra of the elements, as shown below, where we can confirm that effectively, each have their own spectra.

Figure 5. The emission spectra of the elements provide a striking view of the periodic table, highlighting that each element has its own unique spectral fingerprint.

Spectroscopy is a technology based on quantum mechanics, and it is not only employed to determine the chemical composition in samples, but as well it is the main tool to know the chemical environment in astronomical objects, such as our Sun, and the atomic composition in the different layers of the Sun.

Figure 6. Spectroscopy reveals the chemical composition of astronomical objects. The black lines in the Sun’s absorption spectrum correspond to specific elements—such as hydrogen, helium, and oxygen—absorbing light at characteristic wavelengths, allowing us to determine the atomic makeup of the Sun and other stars.

The black lines in Sun’s absorption spectrum are caused by gases helium, hydrogen, oxygen, on or above Sun’s surface that absorb some of the emitted light. Every gas has a very specific set of frequencies that it absorbs.

If a gas is heated to the point where it glows, the resulting spectrum has light at discrete wavelengths that turn out to match the wavelengths of missing light in stellar spectra. Therefore, by studying the spectra of various elements in a laboratory here on Earth, we can determine the composition of the distant stars and beyond!

Figure 7. Visible light spectrum of the Sun (700–400 nm) showing dark absorption lines from elements in its atmosphere, revealing its chemical composition. (N.A. Sharp, NOAO/NSO/Kitt Peak FTS/AURA/NSF)

This image shows the visible light spectrum of the Sun if you used a prism to separate sunlight into its constituent colors. This spectrum was created using the McMath–Pierce solar telescope at the National Solar Observatory on Kitt Peak, near Tucson, Arizona. Astronomers use a large, prism-like instrument to create this extremely detailed view of the Sun's spectrum. N.A.Sharp, NOAO/NSO/Kitt Peak FTS/AURA/NSF

In the image above, the spectrum starts with red light at the top, with a wavelength of 700 nanometers (7,000 angstroms) and ends at the bottom with blue and violet colors with a wavelength of 400 nm (4,000 angstroms). The dark lines throughout the spectrum are caused by absorption of light by various elements in the Sun's atmosphere. This dark-line absorption spectrum is sort of like a fingerprint of the Sun and it provides huge amounts of information about the chemical composition of the Sun and even about the temperature of different regions of the solar atmosphere [1].

When looked at it, doesn’t it resemble a barcode?

From Universal Resonance to Advanced Resonance Kinetics (ARK) Technology

Throughout this article we have seen that resonance is not a marginal curiosity, but a fundamental organizing principle of nature. From the normal modes of a water molecule to the emission spectra of the elements and the barcode-like fingerprint of our Sun, structure and behavior emerge when oscillations become phase-matched and energy is exchanged efficiently between systems. Resonance is the condition that allows “inside” and “outside” to communicate: when frequencies coincide, information and energy can flow, patterns can form, and matter can reorganize.

Advanced Resonance Kinetics (ARK) technology is an explicit attempt to engineer with this same principle. In ARK Technology, specially grown quartz crystals are fabricated as precision harmonic oscillators, designed to vibrate at well-defined frequencies and to couple strongly to electromagnetic modes in their environment. According to recent descriptions, an ARK Crystal functions as a resonant crystal oscillator that taps into quantum vacuum energy—an ever-present background of zero-point field fluctuations—and converts that interaction into a coherent electromagnetic field. This field has a characteristic toroidal (donut-like) topology, with organized electric and magnetic components circulating around and through the crystal, rather than a random, noisy emission.

In this sense, ARK Technology represents “applied resonance”: the crystal is tuned so that its internal vibrational modes resonate with specific modes of the quantum vacuum and with ambient electromagnetic fields, effectively acting as a non-linear amplifier of coherent fluctuations. The resulting high-coherence field exhibits distinct near-field and far-field regions, analogous to the way any antenna or oscillator has zones of reactive, radiative near-field and propagating far-field behavior. For a single ARK Crystal, the dominant vibration corresponds to a wavelength on the order of 0.1 mm, yielding an effective near-field radius of roughly a meter—an interaction volume that can be scaled upward when multiple crystals are assembled into larger resonant structures, such as 64-tetrahedron grids, which extend the coherent field tens of meters.

Because resonance is the mediator of energy and information exchange, such high-coherence fields are proposed to influence nearby systems whose own modes of vibration fall within compatible frequency ranges. In practical applications of ARK Technology, this includes water, biological tissues, and even architectural spaces. Studies and internal testing reports have explored how ARK Crystals may modulate plant growth, support changes in human physiological metrics, or alter the hydration properties of water when the liquid is placed within the crystal’s effective radius, suggesting that resonant coupling can bias these systems toward more ordered, coherent states.

Seen from this broader perspective, ARK Technology is one concrete example of a general principle developed throughout this article: resonance is both a diagnostic tool and an engineering design rule. Spectroscopy “reads” the resonant fingerprints of atoms, molecules, stars, and galaxies; ARK Technology aspires to “write” new patterns of coherence into matter and environments by deliberately shaping the resonant conditions at the interface between material structures and the underlying fields of nature. As our understanding of resonance deepens—from simple mechanical oscillators to quantum-field interactions—the possibility emerges of technologies that do not merely push on matter, but tune it, guiding systems toward states of greater order and functionality through the subtle but powerful logic of resonance.